A letter arrives saying that a friend in Canada was killed in an accident. It asks

me to arrange to have some prayers done for Nina.

The monks at Tengboche are busy, but someone suggests the anis (nuns) at Devuche,

the little nunnery twenty minutes’ walk away. Devuche sits in a meadow at the edge

of the rhododendron forest in a quiet, peaceful place.

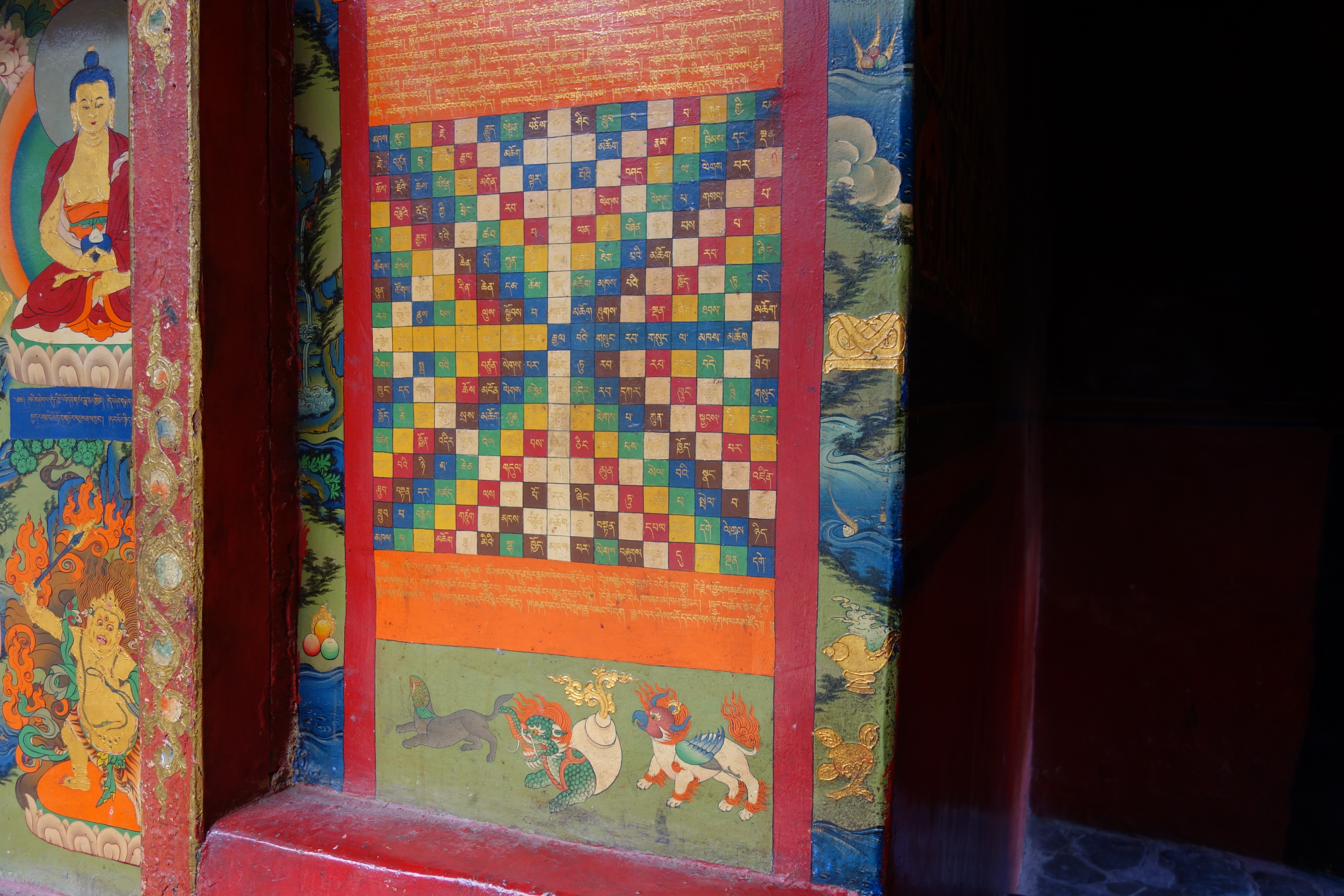

At Devuche, I arrange for the anis to say some prayers the next day. However, in the

morning, only the abbess and one elderly nun are present in the kitchen.

The abbess hands me some of the 50-rupee notes I had given her the day before. “Take

this to the blind ani who can’t come do the puja (prayers) in the gonda but can say

prayers. Take this to the ani in this house right here who is in retreat.”

I knock on the door of the ani in retreat. An elderly person wearing robes and a

traditional winged yellow hat opens the door. I ask, “Would you please say some

prayers for a friend of mine who died 49 days ago?”

She gestures for me to enter. Her small home is clean and tidy. I sit on a wide bench stretching across the end of the room while she prepares tea on the little clay-lined, one-pot burner. She asks the name of my friend who has died. “Ni-na,” she repeats as she notes it down in Tibetan script on an envelope.

“How long have you been in retreat?” I ask.

“Twenty years,” she pauses, “and thirteen years. For this time, I have not left this

little compound.

“I am from Nauche. My family did business in Tibet. When I was eight years old, I

first went to Rongbuk. There I received a blessing from Zatul Rinpoche and took my

first vows to become an ani with Tulshi Rinpoche.

“When I was twenty, I was here in Devuche and had been an ani for several years. A

rich man from Solu wanted another wife after his first passed away. He first sent one

and then two men from Solu to Nauche to ask my mother in Nauche while my father

was in Tibet trading. She sent them away.

“Then, he got several men together — about 11 of them just to come get one woman.

They surrounded my house here in Devuche. I went to bed but could not sleep. Finally,

I escaped out a window late at night and hid in the river gorge.

“They looked in the woods and all the houses. I hid by the river for two days and

on the second night wondered what to do. I had no food, no shoes, just the robe I

grabbed as I crawled out of bed.

“Finally, I worked my way along the river and up through the forest to Tengboche.

Rinpoche could not hide me there, because monastery rules do not allow women to

stay.

“A man who had just come from Tibet a year before agreed to help me. We hid in the day

and travelled at night through Thame and over the pass to Tibet. In those days it took four

days to walk across the Nangpa La (pass) to the first village in Tibet, then ten days to Shigatse and ten more to Lhasa. I stayed there for ten years until I was thirty.

“When the Chinese became really strong in Tibet, I was studying at a nunnery higher

in a valley. Rinpoche and his half-brothers were at a monastery nearby. They came

to see me. We decided it was time to return to Nepal. I came to Devuche and started

my retreat.

“For six weeks after I arrived here in Devuche, we did not know if the Dalai Lama was

alive or dead. Then finally one day I heard that he was in Kalimpong. What a relief.”

As I stand up to leave, I pull another 50-rupee note from my wallet.

“Would you also please do some prayers for the book I’m working on?”

Ani-la holds the bill thoughtfully for a moment before setting it on the windowsill

among her papers.

“People always come and ask me to say prayers for this and for that. So their son

will get into this school or that this business venture will be successful. They do not

understand that when these prayers bring about general good fortune or merit, it

comes from within, from within themselves.”

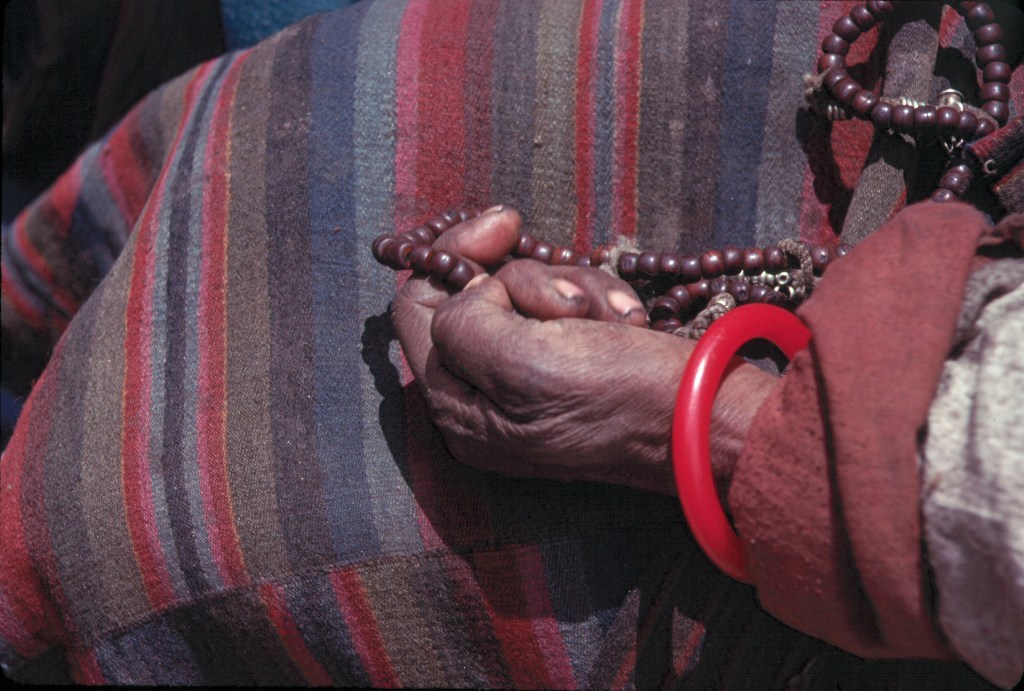

She hands me a paper and a pen.

“I want you to write down these prayers so you can say them yourself for good things

to happen. Om Ah Hung Betza Guru Padme Siti Hung is to Guru Rinpoche. The next is

Om Mani Padme Hung to Chenresig. Om Ah Mi De Wa Hri to Opagme.”

I obediently write down the mantras as she hovers above me in her winged cap.

“Say 108 of each mantra. Say them every day if you can. As you say them, always

think of going to the place of the gods, but always remember…”

She reaches out and touches my chest. “Always remember that the gods are right

here within you.”