From Khumbu to London, celebrations the week of May 29th, commemorated the 60th anniversary of the first ascent of Everest. The celebrations often focus on the two summiteers, Hillary and Tenzing, belying the fact that the actual climb was truly a team effort. While Tenzing was the lead climbing Sherpa, an often forgotten figure is the sirdar, the foreman of the expedition.

From Khumbu to London, celebrations the week of May 29th, commemorated the 60th anniversary of the first ascent of Everest. The celebrations often focus on the two summiteers, Hillary and Tenzing, belying the fact that the actual climb was truly a team effort. While Tenzing was the lead climbing Sherpa, an often forgotten figure is the sirdar, the foreman of the expedition.

“Has my grandfather been completely forgotten?” asks Tashi Sherpa of Tengboche as we sort through a bag of old photographs.

As the then renowned sirdar (foreman) of the 1953 Everest Expedition, Tashi’s grandfather, Dawa Tenzing of Khumjung managed the virtual mountain of supplies, porters, Sherpa high altitude porters, and logistics. He ensured the safe transport of over seven tonnes of supplies and equipment from Kathmandu to Khumbu. The porters he employed represented the wide spectrum of ethnic peoples of eastern Nepal as seen in old expedition photographs.

At the time of the ’53 expedition, Dawa Tenzing (also known as Da Tenzing) was over 40 and was already a veteran of several Himalayan expeditions. Having gone from Khumbu to Darjeeling in search of work as a young man, Dawa Tenzing had memories of the disappearance of Mallory and Irvine on Everest in 1924 according to his bio on the Royal Geographic website.

There is no existing record of his expeditions before 1952, but from 1952–63 records show that Da Tenzing was on several expeditions — reaching the South Col twice in both 1952 and 1953. He was sirdar of the 1955 Kangchenjunga expedition, and again went twice to the South Col with the American expedition of 1963.

During the 1980s, I lived with his daughter’s family at Tengboche where Da Tenzing spent his final years, half paralysed after being injured in the bus accident that killed his wife. One foggy afternoon after his death in 1985, his daughter (Tashi’s mother) emerged from the storage room carrying a large dusty old cardboard box. “Since I cannot read, will you go through this to sort out what might be useful and what we can throw away…”

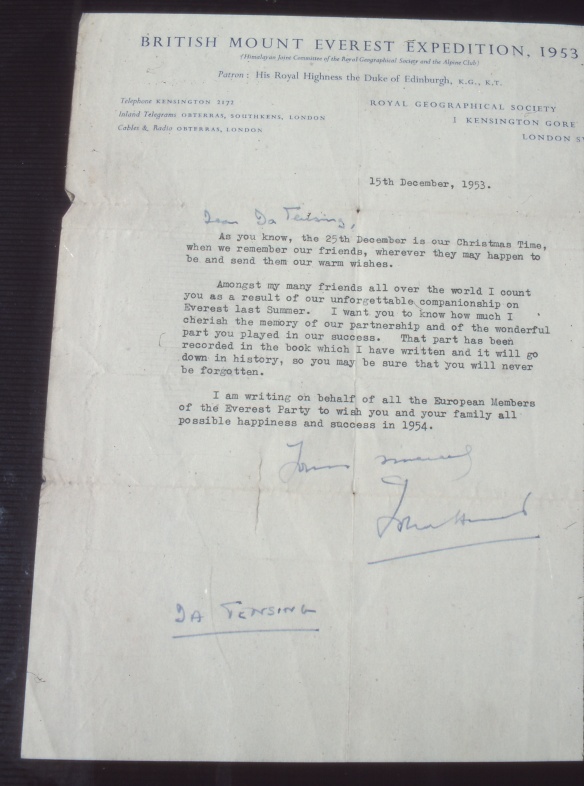

In the afterglow of the 1953 expedition, the British Alpine Club had made Da Tenzin an honorary lifetime member. His remote address had not escaped their mailing list and months later all alpine club mail had duly arrived at Tengboche.

In among the brochures advertising anything from crampons to electric kettles were letters and photographs from the previous generation of climbers from around the world. These included Lord Hunt, with whom he had managed the ’53 expedition, and others from George Lowe to Reinhold Messner.

The photographs revealed Da Tenzing’s close relationship with dozens of expedition climbers from the 1950s onwards. Some showed his attendance at celebratory functions in Britain clad in traditional Sherpa dress and still sporting a long braid wrapped around his head as he met the Queen.

Da, Tenzing spent his last years hobbling around Tengboche monastery as best he could with complete Buddhist devotion. According to his Royal Geographic Society biography, he had “earned respect for his character and his performance as climber and sirdar, and affection for his wicked sense of humor.”

In these 60th celebrations, let’s remember the mountain of men (and some women porters) who made it possible to reach the summit.