Looking at both science and religion or mythology as our way at explaining the universe around us ….

It all becomes relative to time and new observations. In the early 1980s, when I worked in Yoho National Park, we were just beginning to find more about the Burgess Shale fossils high in the Canadian Rockies in beds of shale once laid down as mud on the floor of an ancient ocean.

To introduce these explanations, I would tell the people who came on the guided hides the creation myth of the world by the Blackfoot nation.[1]

In the story, the legendary “old man” is on a raft on the great water or ocean. With him are a loon, a muskrat, and a beaver. He asked each animal to drive down to get some mud from the floor of the ocean. The loon tried but could not dive deep enough. The muskrat tried and tried but also failed. Then the beaver tried. He was gone for a very long time. The old man was about to give up hope when off in the distance, he saw the beaver floating on his back. The old man paddled over the raft to the beaver. There clutched in the beavers paw was a piece of mud. The old man took the mud and rolled it in his hand and created the earth. He spread it out to make the plains. He piled it up to build the mountains. Then, he made the people and the buffalo. Such was how the indigenous people described the creation of their world.2

The story was useful, especially when the students of an evangelical college would come to see the place where they believed that God had touched the earth to stop the great flood. The commonality of water covering the earth in both the creation myth and the biblical story helped introduce the scientific explanation. I would mention that science, religion, and myth are the ways that us humans explain or try to create an explanation at the world around us.

The geological story of the movement of the continental plates on the earth’s surface, of how once 300-500 million years ago, North America was a barren sandy land that slopped off to an ocean a lay its western edge, about where the rocky mountains run today. Eons worth of sand and water layer accumulate at base of an underwater cliff. Layer upon layer, sometimes sand or clay or mud flowed off the cliff to bury the rich diversity of sea creatures. Like on land had not yet evolved. As the Pacific Ocean plate inlet eastwards towards North America these sea sediments this mud from the bottom of the sea.

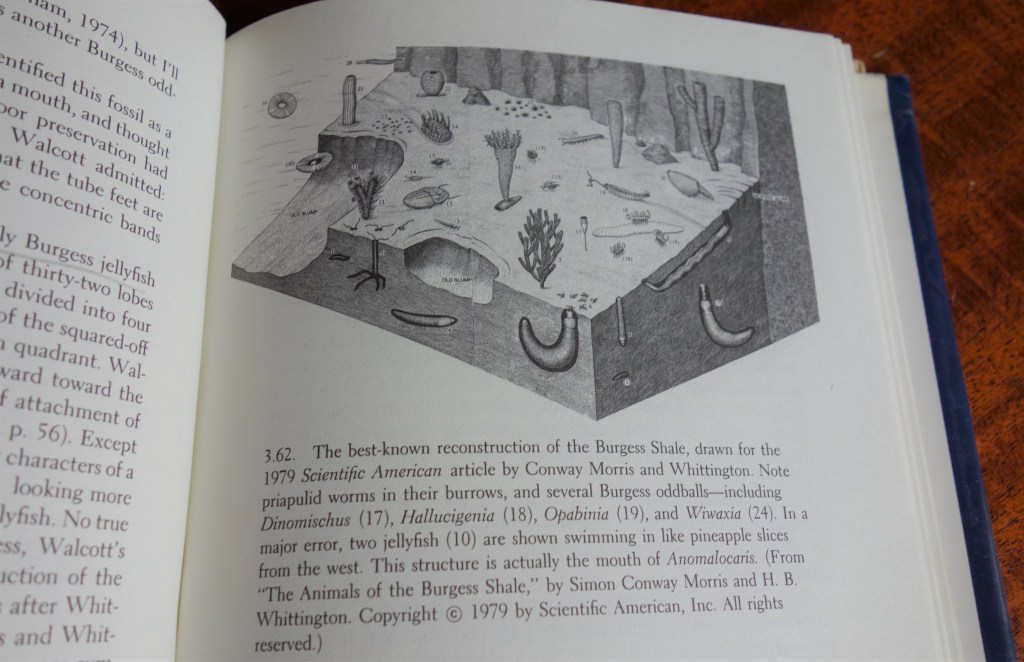

Meanwhile, the explanations of the creatures themselves are fascinating stories. In the early 1980s, the interpretation of two specimens was that they were a small crayfish and the base of a jellyfish. Teams of scientists from the Royal Ontario Museum worked relentlessly examining the shale beds each summer on a mountain side. Those at us working for the national park relayed their interpretation to the public – explaining the trilobites, crayfish, jellyfish, etcetera, in the rich biodiversity of the ancient Cambrian era seas.

In the early 1990s, I returned to living in Canada and began guiding interpretive hikes to the Burgess Shales.

But, the story had completely changed.

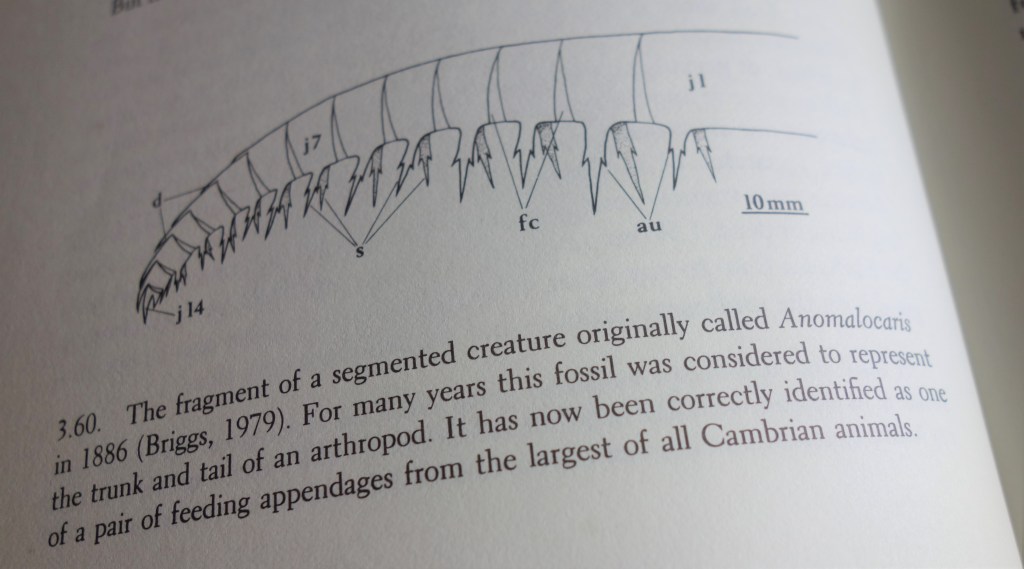

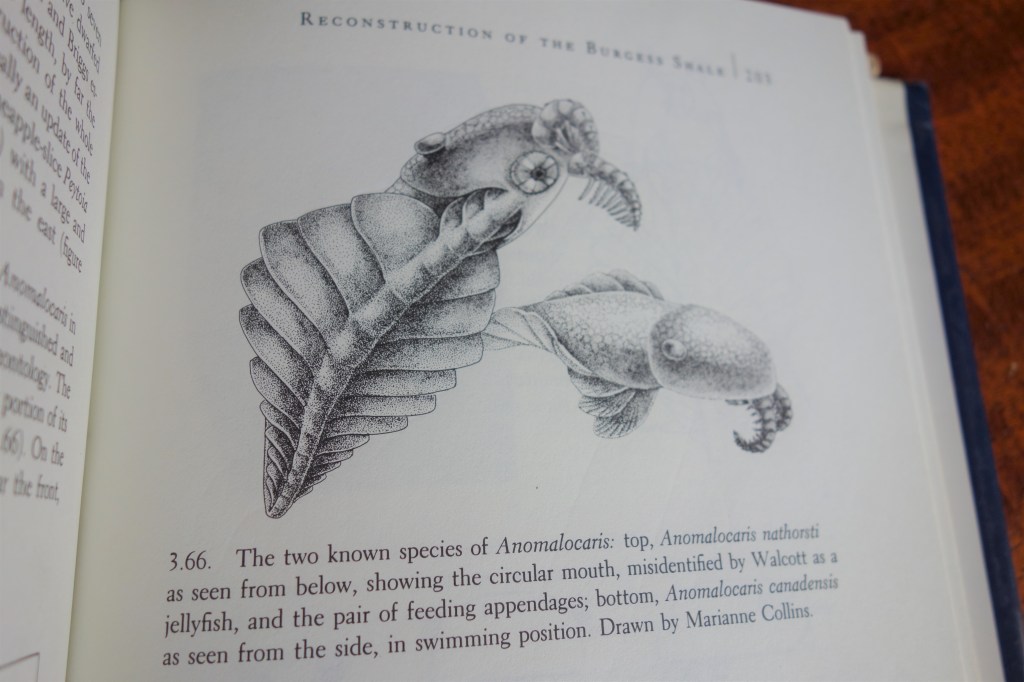

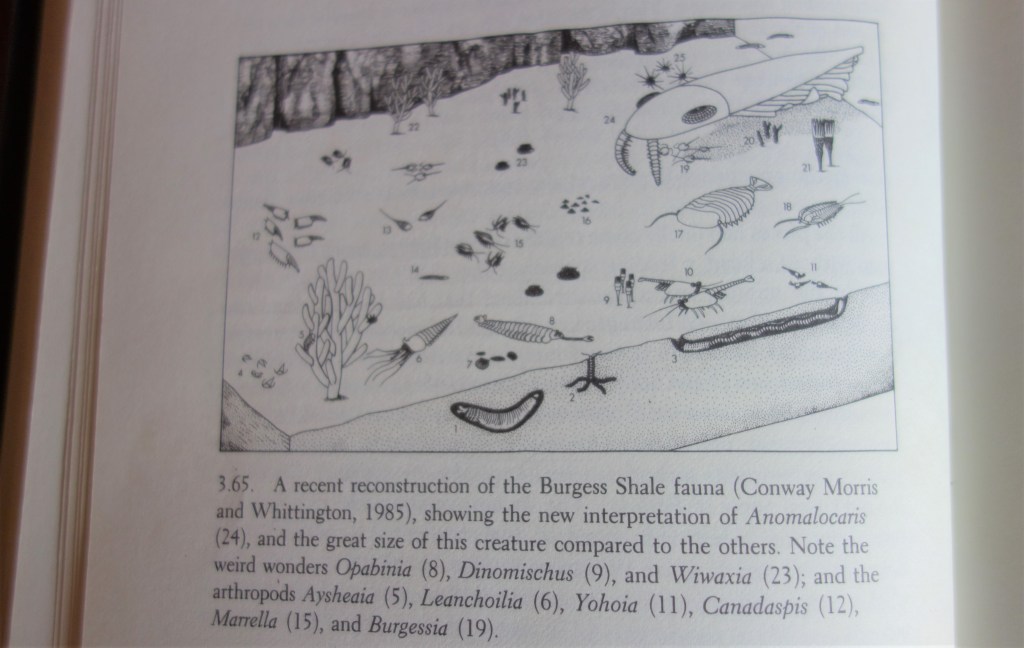

The ‘crayfish’ was found to be the pincer-like arms of a huge fossil 18 inches long. The creature, called Anomalocaris, used these arms to sweep smaller creatures from the seafloor and into its round sucking mouth – which was the fossil previously thought to be the base of the jellyfish.

The ancient crayfish and jellyfish ceased to exist. The scientific explanation had changed.

Stephen Jay Gould described the story of Anomalocaris in his 1989 book Wonderful Life, as “a tale of humor, error, struggle, frustration, and more error, culminating in an extraordinary resolution that brought together bits and pieces of three ‘phyla’ in a singe reconstructed creature, the largest and fiercest of Cambrian organisms.”

Many of the Cambrian animals present had strange body parts and little resemblance to other known animals. Opabinia had five eyes and a snout like a vacuum cleaner hose. Hallucigenia was originally interpreted upside down, walking on its bilaterally symmetrical spines. In 1991, reinterpretations described Hallucigenia as a legged worm-like creature. The tentacles were reinterpreted as walking structures and the spines as protective armor.

The story keeps changing and evolving with discoveries of new outcrops of Burgess Shales and reexamination of the strange and wonderful fossils within. Scientists reconstruct and reinterpret and keep looking at all the possibilities.

While compiling information for the Sherpa museum, conversations had often encompassed aspects of philosophy, psychology, and spirituality, then wandered to the questions we seek to answer with religion or science: How did the earth begin? What happens after death? What is our relationship to nature?

I saw an acceptance of mystery and of questions we just cannot answer. Soon, I realized that one layer of meaning reveals more queries within. The more one starts to understand, the more one realizes all there is to question and explore.

Myths and religion may change with retelling or stay unchanged despite changing times. It is all in our interpretation whether science, religion, or myth.

* Featured image: In 1909, while in the Canadian Rockies near Field, British Columbia, Charles Doolittle Walcott (1850-1927) discovered what has come to be known as the Burgess Shale. Named after Burgess Pass near the location of his discovery, the shale Walcott collected contained carbonized organisms of such abundance and age that they subsequently provided the foundation for study of the Cambrian Period in Western North America. Walcott, fourth Secretary of the Smithsonian, often took his entire family on collecting trips. According to the Smithsonian institution, this image shows Walcott, his son Sidney Stevens Walcott (1892-1977), and his daughter Helen Breese Walcott (1894-1965) working in the Burgess Shale Fossil Quarry, c. 1913.