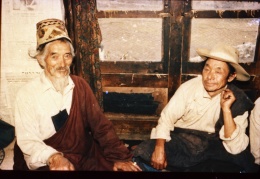

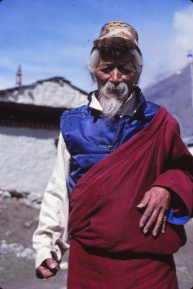

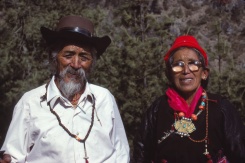

Khonjo Chombi was renowned among the Sherpas as a village leader, for his knowledge of Sherpas folk songs, and his skill as a dancer. He was often asked for his knowledge of Sherpa history and culture so Tengboche Rinpoche had appointed him to be one of my ‘informants’ for the Sherpa Cultural Centre while I worked there in the 1980s.

Khonjo Chombi was renowned among the Sherpas as a village leader, for his knowledge of Sherpas folk songs, and his skill as a dancer. He was often asked for his knowledge of Sherpa history and culture so Tengboche Rinpoche had appointed him to be one of my ‘informants’ for the Sherpa Cultural Centre while I worked there in the 1980s.

Khonjo Chombi is sitting by the window of his house in Khumjung sewing prayer flags onto bamboo sticks.

“Everyone from our clan is putting up new prayer flags today. Then, I have to give a speech at a wedding in Namche. It introduces the two families, even though they’ve known each other for generations.”

“What about your own family history?”

As he continues stitching, he begins, “When people ask about my life story, I first must tell them about my family history.”

Khonjo Chombi pauses as he finds more thread for his needle. “Way back, one ancestor moved from Lhasa to Kham in eastern Tibet, where he settled, practised religion, and had a family.” He then names off successive generations of ancestors for three hundred years.

“In the fifth generation, there was a war between Kham and Tibet. My ancestor, Michentokpa, did not want to fight because it was against the Buddhist tenets to kill any living being. So, he left Kham and first went west to the north side of Everest, then crossed the pass into Khumbu. He may have been one of the first to cross this way into the Khumbu ‘beyul’ (the sacred hidden valley).

First, he settled up high near treeline at Pangboche. This place was like Tibet. Later, his grandson moved south to the Solu valley, to a place called Thakdobuk just below a pass. Our clan name Thakdopa comes from this place. Eight generations later, my family moved to Thame in the Khumbu. After another three generations, my great grandfather moved to Khunde. He had five sons. My grandfather’s marriage was arranged so that he moved into this house as a son-in-law. My father was his only son, and I was my father’s only son.

“My father traded sheep, goats, and ponies throughout eastern Nepal and to Darjeeling in India.” He pulls out a big plastic bag of folded papers, some written in Nepali script and others in Tibetan. He reads aloud from one of the documents dated the Nepali year 1885 (1828 AD).

“This paper from the government in Kathmandu granted us Sherpas a monopoly on the trade route between Nepal and Tibet over the Nangpa La pass. It allowed only Khumbu people to cross the pass. Before the Nepali kings, we paid land taxes to the Kiranti kings in the east and food taxes to the Tibetans.”

on the trade route between Nepal and Tibet over the Nangpa La pass. It allowed only Khumbu people to cross the pass. Before the Nepali kings, we paid land taxes to the Kiranti kings in the east and food taxes to the Tibetans.”

These villages in the remote Khumbu Valley have always been in the nexus of different political authorities, although the Nepali kings ruled since 1769, the Sherpas retained their distinct culture with similar traditions to the Tibetan people to the north. Prior to 1769, various ethnic kingdoms in east Nepal had had enough power over the Sherpas at times to demand taxes or tributes.

Pulling out another paper, he continues, “This list of rules is from the Nepali year 1910 (1853 AD); it also records the taxes collected and how much land people owned. The government in Kathmandu was impressed that my father had dealt with thieves robbing traders in east Nepal, so they asked him to be the tax collector in Khumjung.

Pulling out another paper, he continues, “This list of rules is from the Nepali year 1910 (1853 AD); it also records the taxes collected and how much land people owned. The government in Kathmandu was impressed that my father had dealt with thieves robbing traders in east Nepal, so they asked him to be the tax collector in Khumjung.

“My father performed our Buddhist rituals and treated people with herbal medicines as an amje (traditional doctor). He was also a politician, lawyer, tailor, and carpenter. As a politician and trader, he was sued many times, even in Tibet.

“He had many regrets about having killed people, especially the way he took care of thieves in east Nepal. So when he was old, he left home and became a hermit at the age of 68 and died when he was 78.”

“Did you learn Tibetan herbal medicine from your father?”

“No. My father and the father of Namche’s amje (herbal doctor) trained together in Tibet. My father had many notes for making herbal medicine. When I was four, our house burned down. The notes were lost, so he could not train me as an amje. I always felt this was really too bad, because my father had a cure for smallpox. After he died, the disease struck again twice in Khumbu. Many people died that time. That is when we built the big chorten at the entrance to our village. The second time, the Nepali health worker died first. We buried the body so as not to spread the disease. Later, we were vaccinated by cutting a cross on the skin.”

“Do you remember the first foreigners you ever met?”

“I first saw them when I was trading in Darjeeling and Calcutta. I would normally go twice a year. In the fall, I’d take dzopchioks to Tibet and trade them for Tibetan horses which everyone liked because they were so strong. I’d take the horses to Sikkim or Nepal. I’d also sell Tibetan goods as I went through Solu to the Indian border.

“Finally, I’d go to Calcutta with the money. What a surprise the first time I went. There were people from all over east India and the British with their trains and cars. In Calcutta, I’d buy cloth and corals to bring back to Khumbu and then Tibet.

“When I was young, I wasn’t very business-like. Once, another man and I finished our business in three days and then spent the next two weeks travelling around learning new songs and dances. On those many trips to Tibet, we’d always sing and dance and have a good time with the people where we stayed. Finally we returned to Khumbu before we spent all our money.”

“The first foreigners that I met were on the early climbing expeditions in Khumbu. I met them because I a village headman. For example, I always remember the anthropologist Haimendorf. He stayed with us a long time after arriving in the middle of the monsoon. The time I met the most foreigners was when I went to America with the yeti scalp.”

Khonjo Chombi brings out an old photo album and shows me photographs of his tour in the 1960s. Sir Edmund Hillary had led an expedition in 1964 to view and photograph a yeti, the legendary ‘snowman’ of the Himalaya. Early Western explorers had claimed to have seen huge footprints of a two-legged creature in snow on the high passes.

Sherpas have legends of the yeti. About 350 years ago, the ‘patron saint’ of Khumbu, Lama Sangwa Dorje was particularly fond of a yeti who brought him food and water while the he was in meditation retreat. When the yeti died, the Lama put its scalp and hand bones as relics in the Pangboche village gompa. There is also a yeti scalp in Khumjung gompa.

Khonjo Chombi explains, “The foreigners requested that they be allowed to take the scalp to their foreign lands to show it to their doctors. The villagers agreed if one of us could accompany the scalp on its journey around the world. They chose me to go. The foreigners brought in a flying machine that I’d never seen before. I had to get into the machine – now I know it is called a helicopter. We flew to Kathmandu, where I got into a bigger flying machine, with two other men.

“First we went to England. Here is a photograph of me with the Queen,” says Khonjo Chombi as he points out the picture of himself in his traditional Sherpa garb with a young looking Queen Elizabeth.

“Next we went to New York, then Washington.” He shows a photograph of himself and a US president. More photographs followed of Chicago, San Francisco and the Golden Gate Bridge, Tokyo, and Hong Kong. “They kept looking at our yeti scalp, while I had a good time.”

Just then, a young man enters the room. He tells Khonjo Chombi how he and his wife have lost two babies in the past four years, but they now have a new baby boy. He had asked Tengboche Rinpoche for an auspicious name for the child, and is now here asking Khonjo Chombi to recite the prayers for the child’s naming ceremony.

Khonjo Chombi agrees to come perform the rituals the next day. The man invites me to the party and I accept knowing that to the Sherpas, one helps the host gain merit by receiving their hospitality at these ceremonies.

Both the man and I take our leave. Once outside, he says, “Without Khonjo Chombi we would have so many problems. He tells us the best times to plant potatoes and to dig them; to send livestock to the high pastures, and to bring them down. If there is a quarrel in the village, he is called in to settle the dispute. When he is gone, I don’t know who will be able to replace him.”

Note: Khonjo Chombi passed away in the early 1990s.

This is a lovely story! Are the documents in the library at the monastery?

LikeLike

Thank you for this story about Khonjo Chombi. Family histories are always interesting…his even more so being about Sherpas, and yetis, and Tibet traders, and all things Khumbu!

LikeLike

I’m Khonjo Chumbi’s youngest grandson, after reading this I feel that all his qualities has passed down to the generations. My uncle who is Khonjo Chumbi’s eldest son is one of the top business men in the country. My father shares his love for the Sherpa people as he still helps by being a part of the Himalayan Trust which was founded by Sir Edmund Hillary and is doing a lot for the community till this day. My first Cousin who is raising awareness of how critical Everest is due to global warming and presented himself at ted x about this issue and his solutions and has also sent a rock from Everest to the current president of the United States to build awareness, his older brother who is in love with art and has been no.2 in CNN’s fashion designer to look out for, their youngest brother who has been a physician. My sister who has decided to broaden her knowledge and has completed her masters and myself currently in Sydney and became the youngest active member of a small Sherpa Community here and currently working as an Accountant. All the qualities and the history that you have provided to us today about my grandfather has motivated me to do more. A simple thank you was not enough. I’m very grateful to learn more about my grandfather as I did not have the opportunity to know him as I was born in 1990. Thank you so much this has been very inspirational we shall continue his legend to follow on.

LikeLike

Very nice article by Frances..greatly appreciated your effort to capture those invaluable tales from the elderly people who were the leaders of Khumbu among the older generations..Thank you for doing this..

LikeLiked by 1 person